E42 - Italy's Forgotten Utopia

The most monumental legacy of Mussolini's Italy earned the admiration of even the Dictatorship's most ardent critics, demonstrating that vision need not be incompatible with modernity...

The notion of the perfect society, and the desire to achieve it, has captivated Man ever since his advancement permitted consideration of matters beyond immediate physical need.

It is a drive that has yielded the greatest — and the most terrible — achievements of Man. Arguably, the conviction that there is one path to a perfect society and one alone, irrespective of geography or creed, is among the most ruinous consequences of the French Revolution, and certainly the world which followed the Great War.

Predating either of these, however, is the concept of the città ideale, or ‘ideal city’ — the physical seat of this ‘perfect society’ that would both represent it and encourage its formation. What such a city might look like was a debate that matured in the princely courts of Renaissance Italy. Indeed, the first dedicated text on the subject to be written in the Western world since Ancient Rome, Leon Battista Alberti’s seminal treatise De re aedificatoria (‘On the Art of Building’), was published in 1452.

Nearly five centuries after its publication, the will to realise a perfect society — and a city worthy of it — resurfaced in an Italy where everything, and nothing, had changed. For the Dictatorship of Benito Mussolini was fascinated by the relationship between Man and Building, and by the 1930’s, between Building and City.

The single grandest legacy of that fascination is a place originally called E42, the forgotten venue of a World Fair that never was. Today known as EUR, it is one of the most interesting parts of Rome, despite it being practically unheard of outside Italy.

Today, we tell its story — for it is the story of what happened when Man’s longing for the immortality of his civilisation met the will to realise it…

A World’s Fair

Following the 1922 March on Rome, the first decade of Fascist Italy was characterised by a multi-pronged initiative aimed at stabilising the country following the severe rifts opened by the First World War, due in no small part to the gravely compromised legitimacy of the so-called Liberal State that had managed Italy since 1861.

The consolidation of the Partita Nazionale Fascista under Benito Mussolini as Prime Minister of Italy and Duce of Fascism, its landslide victory in the 1924 General Election, the aggressive crackdown on the Sicilian Mafia from 1925 and finally the negotiation of the Lateran Treaty in 1929, solving the Roman Question and establishing Vatican City as an independent state, were all manifestations of this.

The advent of the 1930’s, however, and the second decade of the Ventennio (literally ‘The Twenty Years’, a term often used in modern Italy to refer to the Fascist era), saw a notable shift in thinking. Now secure, and emboldened by a steadily growing popular consensus, the Dictatorship assumed a greater confidence, and greater ambition in its desire to reshape Italy into a modern power.

It is indeed in the 1930’s when the material face of Fascism, its architecture, began to expand in scope from individual edifices to grand monumental ensembles. The new ‘university city’ of La Sapienza, commissioned by Mussolini in 1932 and entrusted to the visionary guidance of his favoured architect, Marcello Piacentini, was among the first and most spectacular examples of this.

In 1935 therefore, the year the La Sapienza campus was completed, the Duce received with great enthusiasm the suggestion of the Governor of Rome, Giuseppe Bottai, that the Eternal City present a bid for the 1941 World’s Fair. For Mussolini, it was an idea that had landed from Heaven.

On the one hand, it presented an unrivalled opportunity to invite the world to Italy, and showcase what Italian Fascism was able to achieve. On the other, it would allow the creation of a model of inspiration to the Italian people themselves, all while redeveloping the capital.

In 1936, Italy committed, and Mussolini appointed Senator Vittorio Cini to head the Ente Autonomo Esposizione Universale di Roma, the managing body of the whole project. The architect Marcello Piacentini was to assume overall supervision of the design.

The only question that remained now was, how would Fascist Italy present itself to the world?

The Vision

Ten years after the March on Rome, in 1932 Benito Mussolini had committed to written word his vision of the society to which his government aspired. Within this treatise is one passage that succinctly defines the spirit that would be applied to E42:

“Therefore life, as conceived of by the Fascist, is serious, austere, and religious; all its manifestations are poised in a world sustained by moral forces and subject to spiritual responsibilities. The Fascist disdains an “easy” life.

The Fascist conception of life is a religious one, in which man is viewed in his immanent relation to a higher law, endowed with an objective will transcending the individual and raising him to conscious membership of a spiritual society”Benito Mussolini, The Doctrine of Fascism, 1932

“Serious, austere, and religious” are all adjectives that could be applied to E42, the latter both figuratively and literally, for a Christian basilica would occupy pride of place in the planned city, alongside an ensemble of monuments that together demonstrated this “spiritual society”.

Soon after works began, the Italian government, acutely aware of symbolism, rescheduled the World’s Fair to 1942, so that it would coincide with the twentieth anniversary of Fascism, hence the name of E42 — Esposizione Universale del 1942.

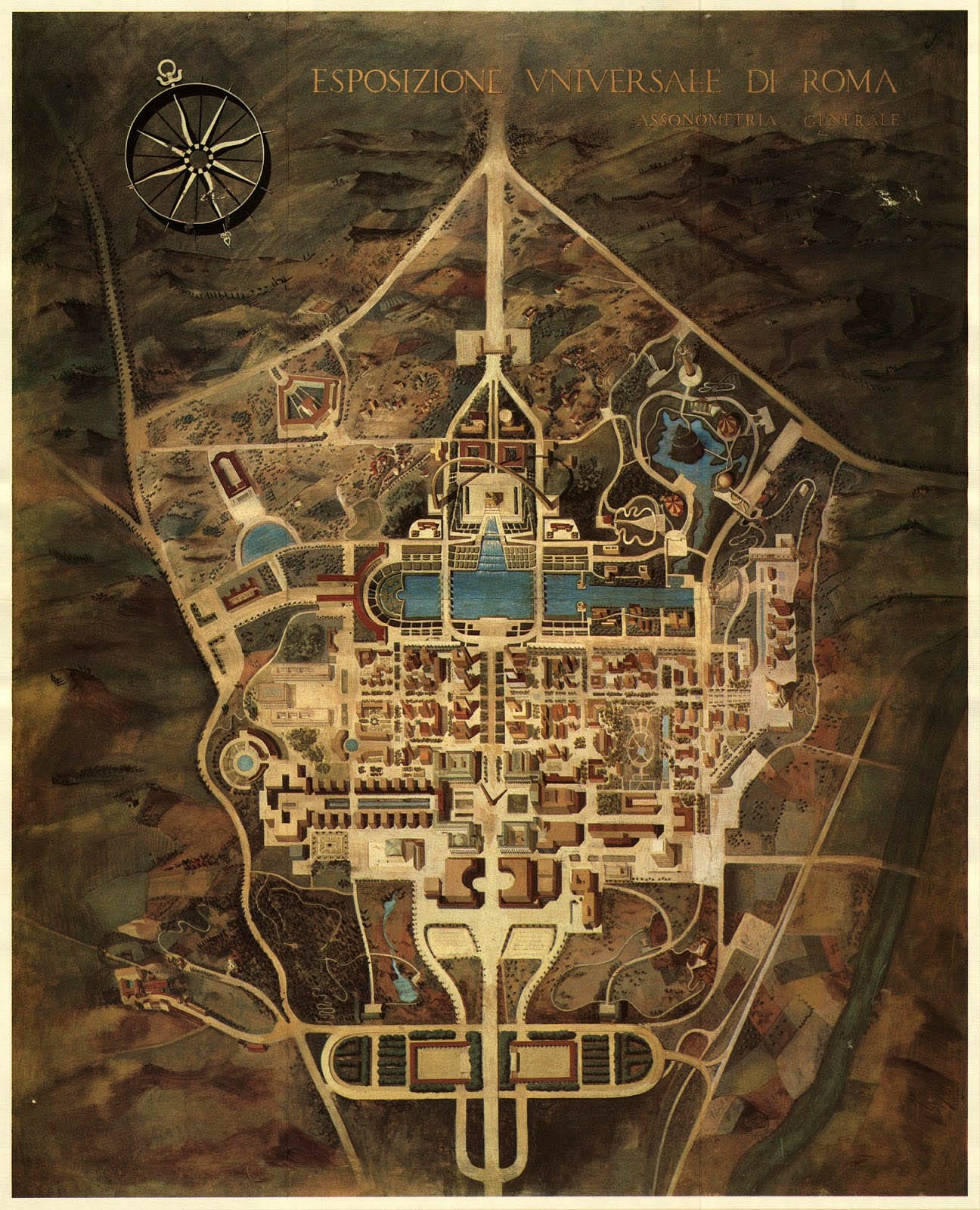

The choice of site for E42 was likewise one laden with meaning as much as practical necessity. Naturally, an undertaking of this scale would have to be located beyond the city centre of Rome. The construction of the La Sapienza ‘university city’ had already demonstrated the wisdom and indeed potential success of developing a ‘polycentric’ city, as opposed to one in which everything of significance occurred in a single centre, with endless sprawl unfolding in every direction.

Mussolini too, was adamant that it was the destiny of Rome to expand the Urbs as far as the shores of the Tyrrhenian Sea. Therefore, both concepts were unified, and a site four hundred hectares in extent was chosen roughly four miles to the south of the Forum Romanum, between the historic centre and the sea. To further emphasise the continuity of the two centres of the old and new Rome, they would be connected by a grand road, the Via Imperiale — today’s Via Cristoforo Colombo — and by the River Tiber, whose course flows directly past E42’s western flank.

Unlike at previous World Fairs, E42 would not be a temporary construction. Following the conclusion of festivities, the major monuments would be retained, while the foreign pavilions were to be demolished to allow the development of the site as a fully-fledged new city. What had elsewhere been fleeting, therefore, would in Italy be an everlasting triumph.

Thus on the 27th April 1937, in a moment of near spiritual reverence, the Duce of Fascism himself opened works on E42 with the planting of an umbrella pine, consecrating the most ambitious domestic enterprise of his government yet. Thereafter, the site was handed over to Marcello Piacentini, and the formidable team of architects and sculptors he had assembled, to raise it to glory.

The chance to design an entire city from scratch is the ultimate dream of any architect or urban planner. Now, we will explore the realisation of just such a dream…

Palazzo Uffici

In late 1937, everything was in place, and Piacentini activated the first part of the E42 plan. Located in the north western corner of E42, the Palazzo Uffici was the first permanent structure of the city to be completed, forming the ‘test run’ for all the others.

Designed by Gaetano Minnucci, and faithful to Piacentini’s masterplan, which took as its inspiration the ‘simplified neoclassicism’ that would define the aesthetic of Fascist Italy, the edifice forms the transition between the outside world and the otherworld of E42. It is indeed here, upon passing the stylised garden of an ancient Roman villa, that the ticket offices for the World’s Fair were to be housed.

As a result, the complex is laden with symbolism that set the scene for the city beyond, especially on the building’s eastern flank.

Contrasting sharply with the cream travertine stone behind it is the bronze statue that Italo Griselli forged in 1939 to depict the Genius of Fascism, where ‘genius’ is understood in the classical mythological sense of an incarnating deity.

As a youthful boy, body honed by toil, industry and combat, his gaze fixed firmly above, crowned with the laurel of victory and striking the Roman salute, he personifies the ideal male envisioned by the Fascist state. After the war, gloves were added to his hands, and the statue was rebranded simply as the Genius of Sport.

Grander still however is the towering bas-relief which accompanies the entrance, and forms one of the most extraordinary examples of propaganda to survive from the Dictatorship. In a single piece, The History of Rome through Building traces the continuity of Rome from her earliest days to the present — from Romulus driving the plough at the summit and the foundation of the Eternal City, to the great works of the Caesars and the Popes thereafter, to Benito Mussolini himself at the level of the viewer, proud upon horseback.

To his right, the soldiery of modern Italy marches before the Duce, bearing the legion eagles of Antiquity. Through Fascism therefore, the viewer understands, the glory of Rome is alive and unbroken.

Palazzo della Civiltà Italiana

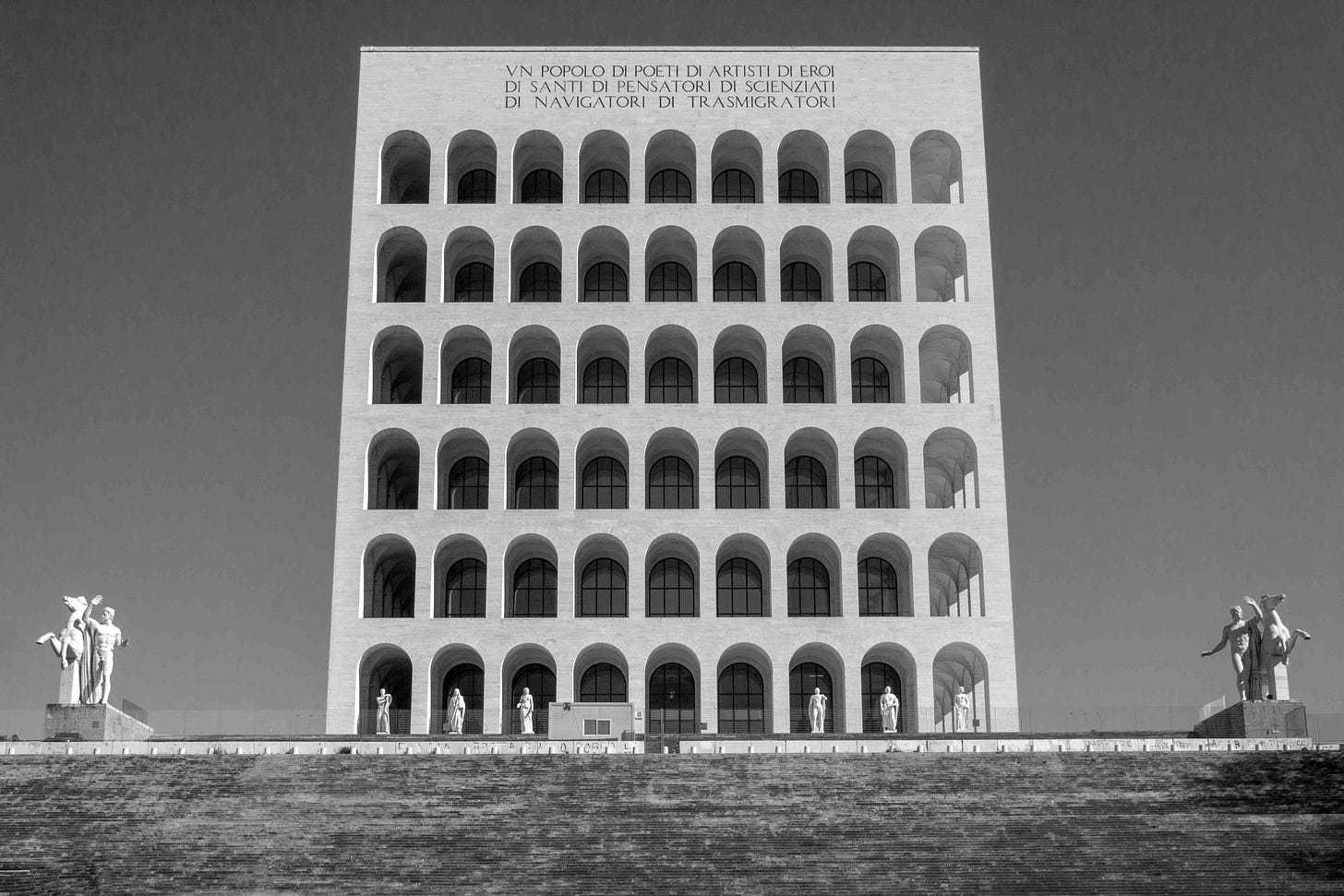

Upon passing the Palazzo Uffici, the visitor is immediately greeted by the sight of what is now the icon of E42, and material emblem of Fascist Italy itself. Officially termed the Palazzo della Civiltà Italiana, or Palace of Italian Civilisation, it is more commonly known as the Colosseo Quadrato, or Square Colosseum.

Begun in 1938 to a design by Giovanni Guerrini, Ernesto Lapadula and Mario Romano under the aegis of Piacentini, there is perhaps no other edifice that encapsulates so immediately both the ethos of E42 and the Fascist aesthetic. It is Rome, grand and confident, yet modern and shorn of her decadence.

Where the Colosseum of the Caesars bore witness to death, that of E42 celebrates the achievements of life, the endurance of the Italian people and all that they had been and thus might one day again be, as the searing inscription that crowns the monument, almost seventy metres above, proudly declares:

VN POPOLO DI POETI DI ARTISTI DI EROI DI SANTI DI PENSATORI DI SCIENZIATI DI NAVIGATORI DI TRASMIGRATORI

“A People of Poets, of Artists, of Heroes, of Saints, of Thinkers, of Scientists, of Navigators and of Explorers”

The 216 arches are arranged such that upon each façade, we see six rows and nine columns, six for the letters of the Duce’s Christian name — B E N I T O — and nine for his last — M U S S O L I N I. Flanking the great monument are the two heroic figures of the Dioscuri, Castor and Pollux, the twin sons of Jupiter who aided the Romans of old in their most trying of hours. Within the arches, a further 28 statues, each exceeding life size, exalt the virtues of the Genius of Italy.

The effect of witnessing this monument today is breathtaking. Had the World’s Fair indeed gone ahead, one can only imagine the power it would have had over Italians and foreigners alike…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to INVICTUS to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.