From Wrath to Redemption

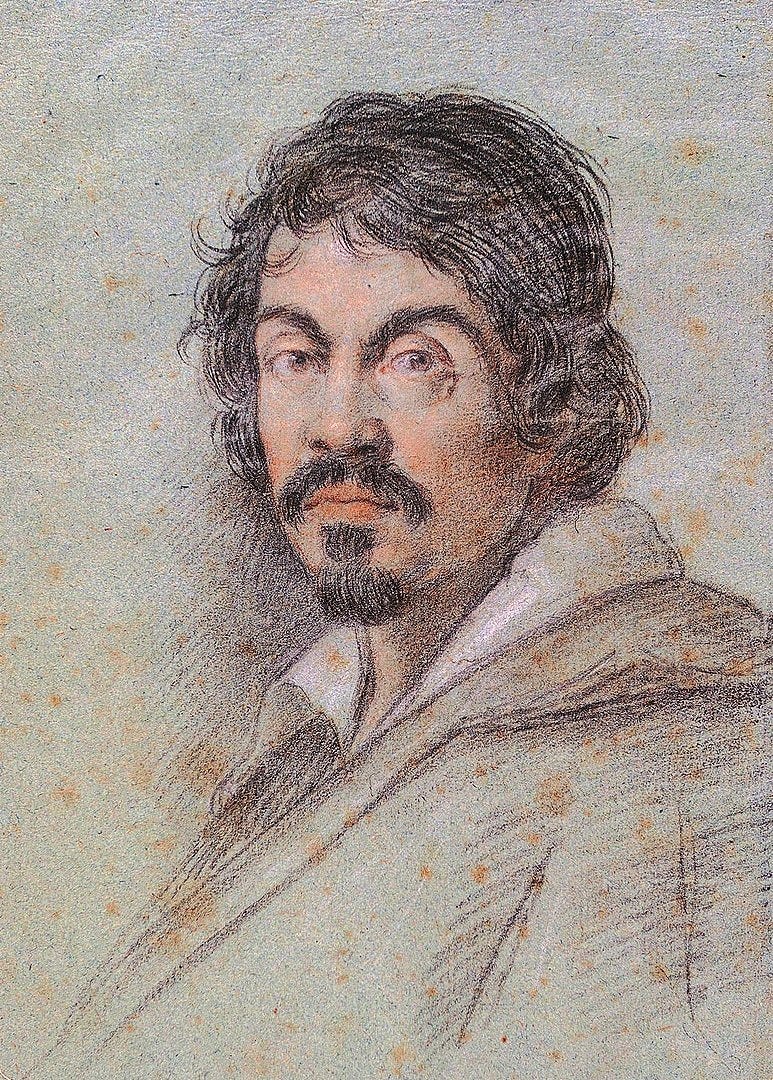

The murder that made Caravaggio a master…

The Baroque master Caravaggio was more than just a painter: he was a fighter, a fugitive, and a man at war with himself. His art was defined by violence, and he painted with the same raw intensity that he brawled in the streets of Rome.

But in 1606, that violence caught up with him. A duel turned deadly, and a man named Ranuccio Tommasoni lay lifeless at his feet. Caravaggio became a wanted criminal overnight, and fled Rome in fear of his life.

Most people focus on Caravaggio’s exile as a tragic fall from grace that left him broken and desperate. But what they don’t realize is this — it was during this time, when he had lost everything, that he painted his greatest masterpieces.

Because when faced with his own destruction, Caravaggio made a choice. Instead of giving in to despair, he instead dedicated the rest of his life to creating beauty — and not just for the sake of fame or fortune, but for the salvation of his soul.

Today, we explore how Caravaggio turned his guilt into greatness — and how you, no matter your mistakes, can do the same.

Exile & Anguish

After the death of Tommasoni, the Roman authorities issued a bando capitale — a legal edict meaning anyone can kill you without legal consequences — against Caravaggio. So the painter fled Rome, and embarked on what would be a long and painful exile.

He went first to Naples, then to Malta, then to Sicily. During this time, the bravado of his early works disappeared, and in its place arose a sort of raw desperation. The arrogance of youth was gone — what remained was the product of a man reckoning with his soul.

But instead of turning to drink or other vices to numb his guilty conscience, Caravaggio turned to his art. His torment was reflected in his paintings, and the first major work of his exile captures this clearly:

Here Christ stands bound to a column, his tormentors caught mid-motion. The suffering is immediate, tangible, and real. There’s no stylization, no idealization — just raw pain. It is the work of a man who was painting to understand his own anguish.

One year later, Caravaggio completed The Beheading of Saint John the Baptist, the only painting he ever signed. It’s a brutal, almost theatrical execution, but its most striking element is his signature — written in the same red paint as the blood spilling from the throat of John the Baptist.

In the early stage of his exile, Caravaggio’s art reflected him grappling with the grief of failure and sin. But that grief would soon give way to the hope of forgiveness, and helped him find meaning in his remaining years…

Death & Resurrection

By 1609, Caravaggio's past sins were beginning to catch up with him, and fast. When he visited Naples in October, he was violently attacked by a group of men and significantly disfigured.

It’s likely the attack was carried out as retribution for someone he had wronged on Malta. But either way, one thing was clear — Caravaggio’s awareness of his mortality was now more acute than ever. He had looked death in the eyes, and was lucky to be alive.

It is perhaps at this point that Caravaggio began to truly understand what it meant to be given a second chance. But for him, that didn’t mean just avoiding death — it meant embracing new life.

His two greatest works during this time, The Resurrection of Lazarus and The Denial of Saint Peter, portray just this. In the former, he depicts a man brought back from physical death. In the latter, a man saved from spiritual death. In both cases, men given new life.

As Caravaggio came to terms with his metaphorical resurrection, he began to understand the purpose of his art, and even his suffering. While nothing could undo his past mistakes, he realized his actions in the present still had a lasting impact on both his own soul, and on those of the men and women who viewed his art.

And so he began, in the words of Pope St. Pius X, “to work in a spirit of penance for the expiation of [his] many sins…”

The Final Journey

In 1610, believing a papal pardon was within reach, Caravaggio prepared to return to Rome. Before setting sail, however, he painted one of his greatest works to date — David with the Head of Goliath.

He sent the painting to Cardinal Scipione Borghese, a powerful figure in the papal court, as both a gift and a final plea for mercy. But what would have been obvious to Cardinal Borghese is often missed to us today — namely, that the severed head of Goliath in the painting is in fact Caravaggio’s own likeness.

To underscore his message, Caravaggio also inscribed the letters H-AS OS — Latin for humilitas occidit superbiam — on the blade of David’s sword. The inclusion of this phrase, meaning "humility overcomes pride,” is key to understanding Caravaggio’s spiritual growth: the monstrous giant of his pride had finally been put to death.

Caravaggio boarded a ship bound for mainland Italy, but fate had other plans. He fell ill along the journey, and died at the age of 38 in Porto Ercole, Tuscany — far from the city he longed to see again. News of his official pardon arrived shortly after his death.

Yet while Caravaggio’s search for earthly redemption was left incomplete, the fruit of his exile soon became evident. The pieces he produced while wrestling with his grief, guilt, and anguish are counted among his most powerful works, unrivaled in their depiction of the Biblical drama.

Where others would have collapsed under the weight of their past mistakes, Caravaggio instead channeled his guilt to drive him to greatness — he was no longer painting for himself, but for the salvation of his soul.

Takeaways

1) Recognize Where You’re Wrong

Be honest with yourself and don’t downplay your past mistakes. If Caravaggio had tried to diminish the magnitude of his sin (murder), he never would have had a chance at redemption.

Even the gravest of mistakes can be vehicles for transformation — but that transformation will never happen if you don’t admit where you’ve gone astray.

2) Channel You Grief into Purpose

Caravaggio's profound remorse became the driving force behind his most impactful works. Instead of succumbing to despair, he harnessed his guilt to fuel his creativity.

The way you respond after failure is crucial. When faced with regret, don’t use it as an excuse to waste away, but as a catalyst to propel yourself toward what is meaningful.

3) Work for the Eternal

Everything you do, even your worst mistakes, can serve to benefit others. Caravaggio knew he could never bring the man he killed back to life — but he could serve as an example to others.

While in exile, Caravaggio had his mortality at the top of his mind, and painted as if eternity depended on it. The result? A body of work that has inspired untold numbers of Christian believers throughout the world, and which endures well over 400 years after its creator’s passing.

Want to dive deeper?

If you’d like to explore the streets Caravaggio walked before his exile, be sure to join us on our summer retreat to Rome! He will be one of the main figures we cover on the day dedicated to Rome’s Baroque Age.

This Thursday at 9am ET, James and I go live on X to discuss the tumultuous life and career of Caravaggio. Visit my X account at 9am to access the livestream — once it ends, the stream will be added to our Members-Only Video Archive for you to catch the replay.

Also this Thursday, our premium subscribers will get a deep dive article on Caravaggio’s painting The Seven Works of Mercy — a tormented and dramatic guide to living the life of virtue…

If you’re not already a premium subscriber, please consider joining below — and don’t forget that members of our Praetorian Guard get 5% off on retreats, and priority selection for attendance!

Ad finem fidelis,

-Evan

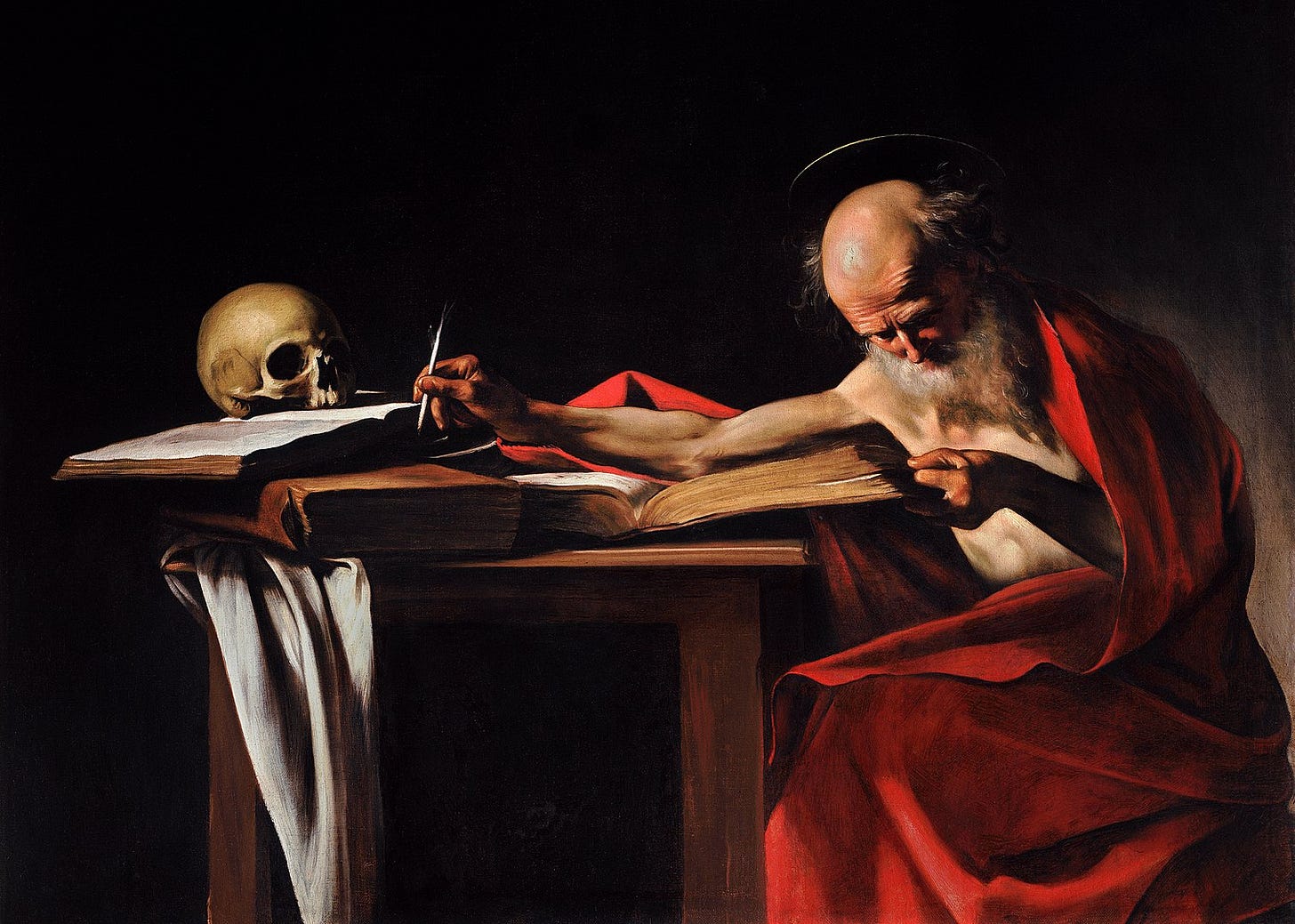

We've just studied this painting a few days ago, in our art history class. Awesome read, thank you!