The Architect of Fascist Italy

Italy's foremost architect of the 20th century remains largely unknown in the English-speaking world, but his influence would reach the imagination of millions...

Marcello Piacentini is not a name that enjoys broad recognition in the English-speaking world. The reason for this, however, is not because his works were obscure or few in number. On the contrary, the legacy of one of the most influential architects of the 20th century is manifold and monumental.

As the architect of the built aesthetics of Fascist Italy, however, Piacentini has long been persona non grata in the considerations of the victorious belligerents of the Second World War, where the mildest praise for anything that occurred in Italy between 1922 and 1943 is traditionally taken in immediate bad faith as a wholesale endorsement of all the policies of the Fascist government, triggering an automatic tripwire of condemnation.

In Italy, however, the matter is rather more nuanced, as while he certainly enjoyed the favour of the Duce and support of the authorities, the career of Marcello Piacentini flourished long before and after the Dictatorship, being motivated by, in his own words, a desire to make architecture “adapt to the tastes and needs of citizens”.

Indeed the success of Piacentini lay in an extraordinary ability, over the course of fifty years, to balance an admiration for the past with the pressure to modernise, to create something that was visually fresh, yet substantially rooted.

Here is how Marcello Piacentini squared the circle of conservation and innovation, and bridged the old and new worlds of architecture…

From Architect to Urban Planner

Born in Rome on the 8th December 1881, Marcello Piacentini would mature in the cultural blossoming that was the European Belle Epoque, or as it was known in Italy, the Umbertine Era, coinciding as much of it did with the reign of Italy’s second king, Umberto I (r. 1878-1900).

For the visual arts, it was a banquet, and Marcello would have a prime seat at the table. After all, his father Pio Piacentini was himself a lauded architect who had designed the Palazzo delle Esposizioni, the first great cultural venue of Rome to be built after the unification of Italy, and who in 1905 would play a significant role in the construction of the mighty Altare della Patria, the Monument to Victor Emmanuel II that towers over the ancient core of the Italian capital today.

Thoroughly grounded in an upbringing defined by a reverence for the classical past, Marcello Piacentini would hit the ground running. Aged just twenty five, in 1906 he qualified with full marks as professor of drawing at the Royal Institute of Fine Arts. The same year, working alongside engineer Giuseppe Quaroni, he would win his first commission, to design a new mental health hospital in the city of Potenza. While the so-called Ophelia project would be plagued by bureaucratic issues, a far greater springboard came shortly after, when in the following year Piacentini and Quaroni won a public selection to redesign the città bassa (‘lower city’) of Bergamo.

Their proposal, called Panorama, had particularly impressed the judges on account of Piacentini’s clear respect for the historical urban fabric of the city. At the same time, the planned structures, from banks to post and telegraph offices, felt original while still having the appearance of something that could have been built in the 15th century, rather beautifully reconnecting Bergamo to her flourishing days under the Venetian Empire.

Piacentini’s commitment to the project, too, was extraordinary. Following the preparatory work, construction began on the first edifices in 1912, and ended with the last in 1927. Throughout the entire period, the architect remained in close contact with the authorities, long after achieving international fame and even while working on scores of other commissions in Rome, modifying the design as per evolving need. One such modification, for example, would be the addition of a memorial tower, the Torre dei Caduti (literally the ‘Tower of the Fallen’ — pictured above), after the Great War, which Piacentini personally designed and completed in 1924.

It is a mark of the success of Panorama that the popular district is still today known as the Centro Piacentiniano. It was indeed an immediate success, establishing Piacentini’s credibility as both architect and urban planner, and what would become his trademark — an ability to bridge modernisation and conservation in a manner which complimented, rather than contrasted, its surroundings.

Brussels, Benghazi & Breakthrough

Alongside his father, Piacentini would work on a number of public and private commissions over the years to come, bringing his ‘tamed modernity’ to the villas of affluent Romans. Amid such rising prestige, it would not take long for his name, and person, to travel abroad.

In 1910, Piacentini designed the Italian Pavilion for the World’s Fair in Brussels, winning the Grand Prix in architecture and international respect. One year later, he would consolidate this in the extraordinarily grand temporary monuments he built in Rome for the fiftieth anniversary of Italian Unification, demonstrating his competence for Beaux-Arts and lavish Baroque — a facet of Piacentini often overshadowed by the more famous aesthetics he developed under the Dictatorship.

Buoyed by success after success, following Italy’s military victory over the Ottoman Empire in 1912, and extension of her own colonial empire in North Africa, Piacentini was appointed Superintendent of Construction for the newly founded colony of Cyrenaica (today’s eastern Libya).

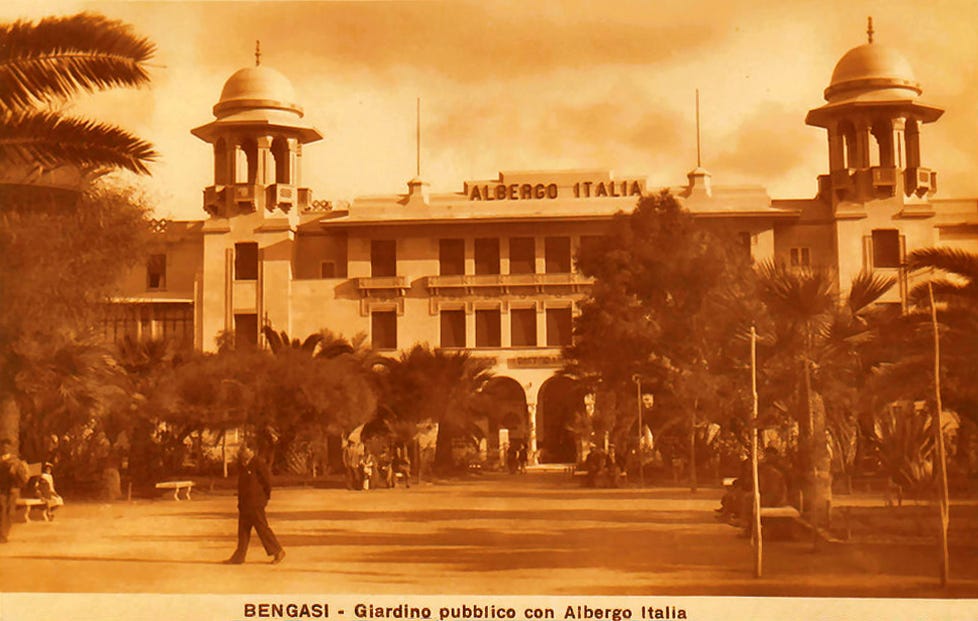

There Piacentini would play a major role in shaping the old Ottoman town of Benghazi into the capital of the new colony. His trademark philosophy adapted Italian architecture to the context of the Maghreb, incorporating Moorish flourishes to the Grand Hotel Roma, and indeed later the town hall itself.

Rather like in Bergamo, Piacentini would leave a lasting legacy in Benghazi built over the course of years, culminating in the Teatro Berenice, a glamorous centrepiece of the city waterfront that proved popular among Libyans well after independence, and whose destruction in the wake of the 2011 civil war triggered widespread local and international outrage.

The Third Way

By the time of the March on Rome, and the ascent of Benito Mussolini to the premiership of Italy in 1922, therefore, the reputation of Marcello Piacentini was already bolstered by an impressive list of celebrated achievements both at home and abroad. His own repertoire, in turn, began to evolve along with his travels and exposure to contemporary trends in the United States and northern Europe.

Quite apart from his many commissions, Piacentini was beginning to exert significant influence over the philosophy of architecture in Italy. By the 1920’s, the debate between modernisation and conservation consolidated into two highly vocal opposing camps — the Razionalisti, or Rationalists, who followed the emerging international line that buildings should scorn decoration in favour of function, and the Movimento Novecento, which advocated a return to the traditions of classicism.

Marcello Piacentini however would skilfully bridge both of these with a third option — neoclassicismo semplificato, or ‘simplified neoclassicism’ — offering something grounded in the deepest roots of Italy’s culture, while staving off potential criticism that he was merely copying the past. It is this, therefore, which endeared Piacentini in particular to Mussolini.

The Duce wished to reforge the nation as an innovative modern industrial power — yet whereas the Bolsheviks had relished the destruction of Russia’s past, Fascist Italy would be both conscious and proud of her position at the head of thousands of years of achievement. The new aesthetic of Italy had to establish a break from the pre-1922 Liberal State, while still being uniquely Italian. In Piacentini, Mussolini would find precisely the man to share this ambition.

In 1923, Piacentini was appointed to the Construction Commission of the City of Rome, and from this moment on there was scarcely a moment in his life when his growing studio was not overseeing multiple projects simultaneously, in the capital, across the Italian Empire and abroad. The period would be opened by the grand Arch of Victory in Genoa, which married both the Ancient Roman and Renaissance Triumphal Arch in a majestic memorial to the city’s war dead.

The following year would see his first major imprint on Rome herself, when he was commissioned to build the Casa Madre dei Mutilati e delle Vedove di Guerre as a new headquarters for the National Association of the Mutilated and Invalids of War. Situated between the Palace of Justice and the Castel Sant’Angelo on the Tiber embankment, the Les Invalides of Rome occupies prime position in the Eternal City.

This ‘third fortress’, somewhat echoing the towering gatehouses of the Aurelian Walls, also forms a clever transition between the imposing brickwork of the castle and extravagant neo-Baroque of the High Court. In addition to stylised classical motifs and the juxtaposition of both Latin and modern Italian inscriptions, Piacentini’s choice of brick, tuff and travertine — the favoured building materials of Ancient Rome — was a powerful statement of the new ‘rooted modern’ vision that Piacentini shared with Mussolini himself.

Between his 1925 proposal for Grande Roma and a swathe of projects across the capital (including the Albergo Ambasciatori and Palazzo del Ministero delle Corporazioni on Via Veneto) Piacentini had more than enough work to keep him occupied. Yet still, he aspired to more ambitious visions of urban redesign.

Fortunately for him, so too did the Duce — as a result, the 1930’s in Rome would be dominated by precisely these…

The New Italy

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to INVICTUS to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.