The Pope Who Saved Rome

After over a century of turmoil in Western Christianity and anarchy in central Italy, in 1420 Pope Martin V reunified the Church and restored Rome to glory

The destinies of Rome and the Catholic Church are so intimately intertwined that one cannot today consider one without the other. For each has brought everlasting glory to the other, in a city where the succession of the Caesars wed that of the Apostle Peter, in a union whose prestige has known no equal in the annals of history. The notion of their separation is inconceivable.

Yet for much of the 14th century, such a dread scenario indeed came to pass, as the Popes dwelled not in the Eternal City but in the south of France, with little hope of ever returning. It was the great ‘Babylonian Captivity’ of the Church, with the Vicariate of Christ reduced to a vassal of the French crown.

But then, 1,000 years after the collapse of Classical Antiquity, and as Christendom lamented what appeared to be the second fall of Rome, one man more than any other saved the cause of civilisation in the West. His name was Oddone Colonna.

Were it not for him, and his election in 1417 as Pope Martin V, the glories of Renaissance, Baroque, and Neoclassical Rome might never have been realised.

What follows is the story of how a Pope saved Rome…

But first — this summer we are hosting our first ever INVICTUS retreat, The History of Rome as Told by Its Heroes.

Click here to learn more about the retreat and how to apply today. If you love the Roman Empire and the Eternal City, you do NOT want to miss this…

The Babylonian Captivity

In the year 1300, the city of Rome embodied a splendour scarcely known since the Caesars. For on the 29th June, the Feast of Saints Peter and Paul, Pope Boniface VIII called the first Jubilee, and presided over a city that was truly the heart of Christendom.

Pilgrims from across Europe and as far away as distant Asia flocked to the See of Peter in such breathtaking numbers — some 200,000 by one account — that sections of the ancient Leonine Wall had to be torn down to accommodate their flows. Day and night, for months on end, endless throngs lined the streets for a chance to pay homage at the tombs of Apostles and Saints alike, in a city whose name transcends all others in earthly glory.

Yet it would be a fleeting illusion. For when Boniface denounced King Philip IV of France for seeking to alleviate his financial woes through punitive taxes on the clergy — and reminding him that the authority of Rome is placed over that of kings and kingdoms alike — a near existential disaster was unleashed on the Church.

Set upon by allies of the French, the Pope was famously struck in the face in September 1303 by Sciarra Colonna, and succumbed to his brutal treatment weeks later. His successor, Benedict XI, scarcely outlived him, and in 1305 King Philip leveraged his influence to have a Frenchman, Raymond Bertrand, elected as Pope Clement V and crowned at Lyons.

A Frenchman first and clergyman second, Clement spurned Rome and took up residence in Avignon in 1309. In less than a decade, the Eternal City had fallen from adulation to abandon.

A Rome in Ruins

The sixty eight years that followed Clement’s fateful decision of 1309 would be the nadir of Rome’s fortunes.

As if to consecrate this unholy disaster, mere weeks after the city was vacated by the remnants of the Curia a terrible fire ravaged the Basilica of Saint John Lateran, the mother church of Western Christendom, and the palace adjacent — an edifice which had been the seat of the Papacy since the days of the Emperor Constantine.

In the absence of her shepherd, Rome collapsed into violent anarchy, as the feuds of the now unchained Roman barons spilled into the streets with bloodthirsty fury. The squalid streets overflowed with refuse and were punctuated by bodies, as cadres of armed men on the payroll of the Orsini, Colonna, Frangipane, Savelli and other families dictated the law now.

Robberies were common, and even the most devout pilgrims balked at the city’s exploding reputation for crime. Others wailed in lamentation, scourging their own flesh upon the streets as flagellants.

“Behold Rome, once the empress of the world, now pale, with scattered locks and torn garments”

Petrarch, Letter to the Holy Roman Emperor Charles IV

Such were the words of the greatest scholar of the 14th century to the Emperor Charles IV, driven by love of what Rome had been, and desperate to see her restored as caput mundi once more.

To the many woes of Rome, however, were added twin scourges upon her people and her urban fabric. For in 1348, the Black Death carried off a terrible proportion of her citizenry, before a devastating earthquake on the 9th September of the following year inflicted perhaps the most severe losses on the physical city since the Vandals.

Entire edifices crumbled before the power of the seism, both palaces and towers alike. The roof of the beleaguered Lateran crashed to the ground, along with the bell tower of Saint Paul Outside the Walls. But in arguably the greatest calamity, the brunt of the ruin was borne by the ruins of Ancient Rome.

Scarcely a monument in the Forum escaped laceration, but, to the despair of Petrarch, none compared to fate of the Colosseum, whose entire southern façade collapsed onto its foundations. It is this terrible event, along with the pillaging of her stone that followed, which more than any other has robbed us today of the wonder that the greatest symbol of Rome once truly was.

Thus did the Eternal City, which had entered the 14th century amid a vision of greatness, depart it the image of beggary. So too did Christendom itself, as the fallout of Avignon saw her leadership fracture into Papacies, Antipapacies and apparently interminable disgrace.

The Redemption

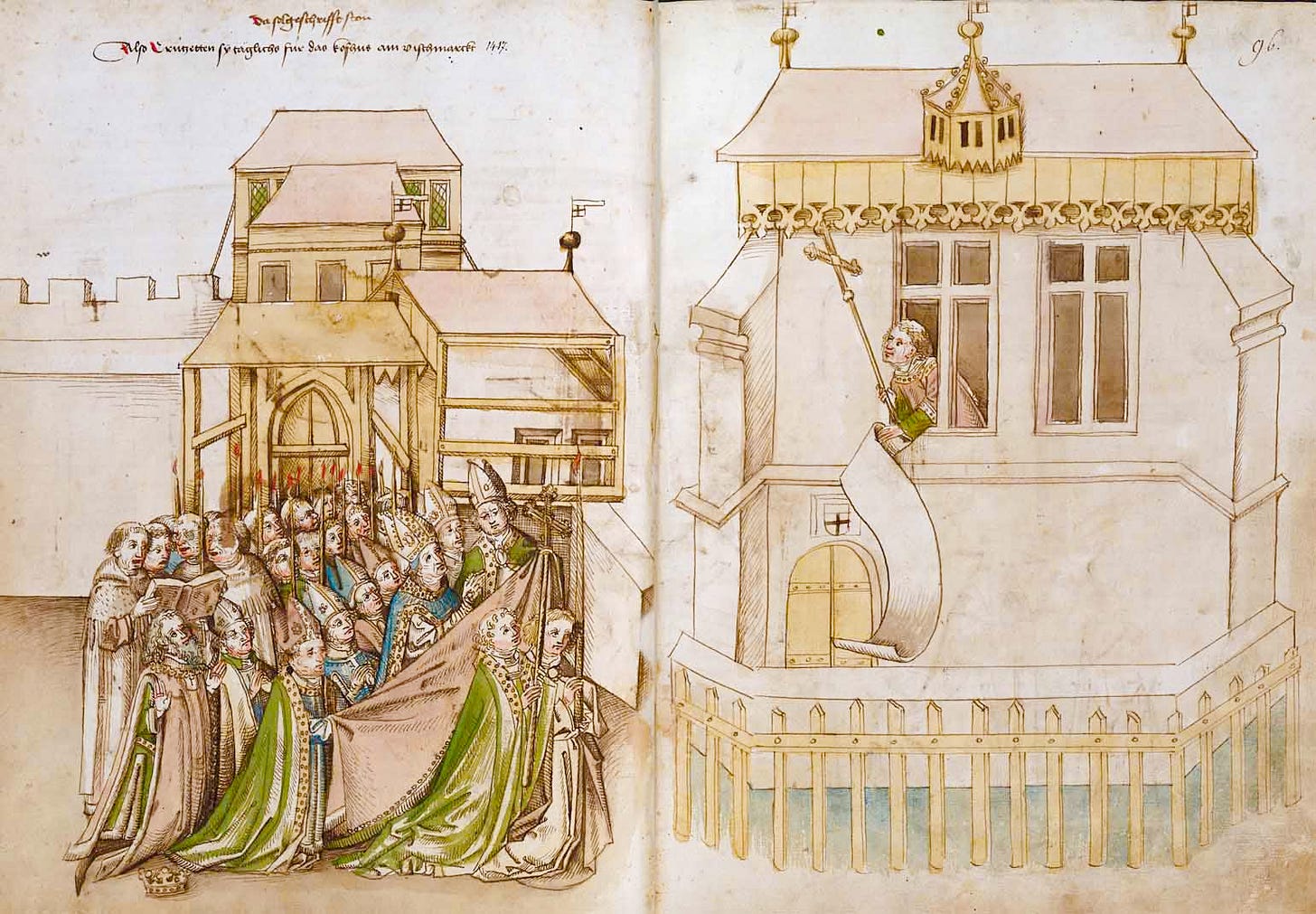

In 1417 however, tentative hope was kindled at last with a new cry of Habemus papam.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to INVICTUS to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.