The Trevi Fountain and the Glory of Rome

The world's most famous fountain is an architectural triumph, yet so too a celebration of Roman continuity, and power over nature...

Turn east off Via del Corso, or south from Via del Tritone, and you will soon hear it. At first, as a gentle rumble — then, upon entering the piazza at the lower slope of the Quirinal Hill, a thunderous roar.

By sun or moon, the sight that accompanies the all-consuming din is one never to be forgotten. For of all the celebrations of Man’s mastery over water, and his commitment to the beautification of his city, few can match the greatest of the fountains of Rome.

Yet the Fontana di Trevi is more than a banquet for the eyes and concert for the ears. Superficial beauty absent of meaning, after all, is the definition of tasteless, and refinement has long been chief among the exports of Italy to the world.

Indeed this magnificent wonder, at once sculpture and architecture, is a celebration of Rome herself — what she had been, what she endured, and what, well-governed, she might again be.

What, therefore, does the Trevi Fountain truly mean to the Romans?

The Virgin Aqueduct

As the product of the Late Baroque and Rococo worlds of the 18th century, the Fountain we see today is merely the crowned head of a long body of history, one whose roots burrow deep into Antiquity.

While the transportation of water by aqueduct had already been practised by the Minoans, it was the engineering of the Ancient Romans that overcame the challenges of unsteady terrain, and allowed the mass supply of cities. It would not be long before the monuments of Rome swelled as a result of such ability, and in 19 BC Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa, the favoured lieutenant of the Emperor Augustus, was in need of a water supply for the grand bathhouses he had constructed — the ruins of which are found directly behind the Pantheon.

Thus to feed said Baths, the general erected at his own expense Rome’s sixth aqueduct, the Aqua Virgo. It snaked around the northern flank of the city walls — possibly to avoid the complications of securing private property — to its source eight miles beyond the urban limits to the east, roughly halfway between the centre of Rome and modern Tivoli.

According to the 1st century AD engineer and writer Sextus Julius Frontinus, whose extensive survey of the Rome water supply survives today, the Aqua Virgo took its name from the maiden, or virgin, who had reportedly revealed the source of the water to Agrippa’s soldiers.

Unlike many of the other aqueducts, the course of the Aqua Virgo was almost entirely underground, and breached the surface only for its final kilometre. As a result, the water it provided was widely celebrated for its purity from the outset. Indeed, even half a millennium later, the writer Cassiodorus extolled its virtues, offering another theory behind the name of the ‘Virgin Aqueduct’:

"Purest and most delightful of all streams glides along the Aqua Virgo, so named because no defilement ever stains it. For while all the others, after heavy rain show some contaminating mixture of earth, this alone by its ever pure stream would cheat us into believing that the sky was always blue above us”

Cassiodorus, Variae, VII.6

Indignity and Ruin

As Rome declined in the West, and what remained of her imperial power withdrew to Constantinople, her great monuments fell into disrepair and indignity. Starved of the will to maintain it, so too did her essential infrastructure.

Many of the city’s eleven aqueducts would be deliberately cut by the besieging armies of the Ostrogothic warlord Vitiges in AD 537, and fall permanently into disuse. The largely subterranean Aqua Virgo, however, clung on to existence — even if by the onset of the Middle Ages, the final overground section had ceased operation.

As the glory of Rome faded into the memory of fathers, then grandfathers and thereafter distant ancestors, the Latin Aqua Virgo was corrupted into the Italian Acqua Vergine, and its flow, impeded by an ever more onerous build up of detritus, withered to a trickle.

By the sunset of the 14th century, with the Church itself having vacated Rome, it was said that such was the ignorance of the Romans that if the ordinary man chanced a gaze upon a ravaged aqueduct, he did so oblivious to its former function.

Yet with the healing of the Western Schism, and the definitive return of the Papacy to the Eternal City in 1420, Rome, too, began to heal from a thousand years of decay. With the population rapidly recovering from the abyss, the old Campus Martius began to know hustle and bustle again.

The vicinity of the maimed head of the Acqua Vergine would form a natural point of congregation, particularly at the heart of a district known since the 12th century as Regio Trivii, on account of the crossroads of three streets — trivium in Latin, tre vie in Italian — located there.

Function to Adornment

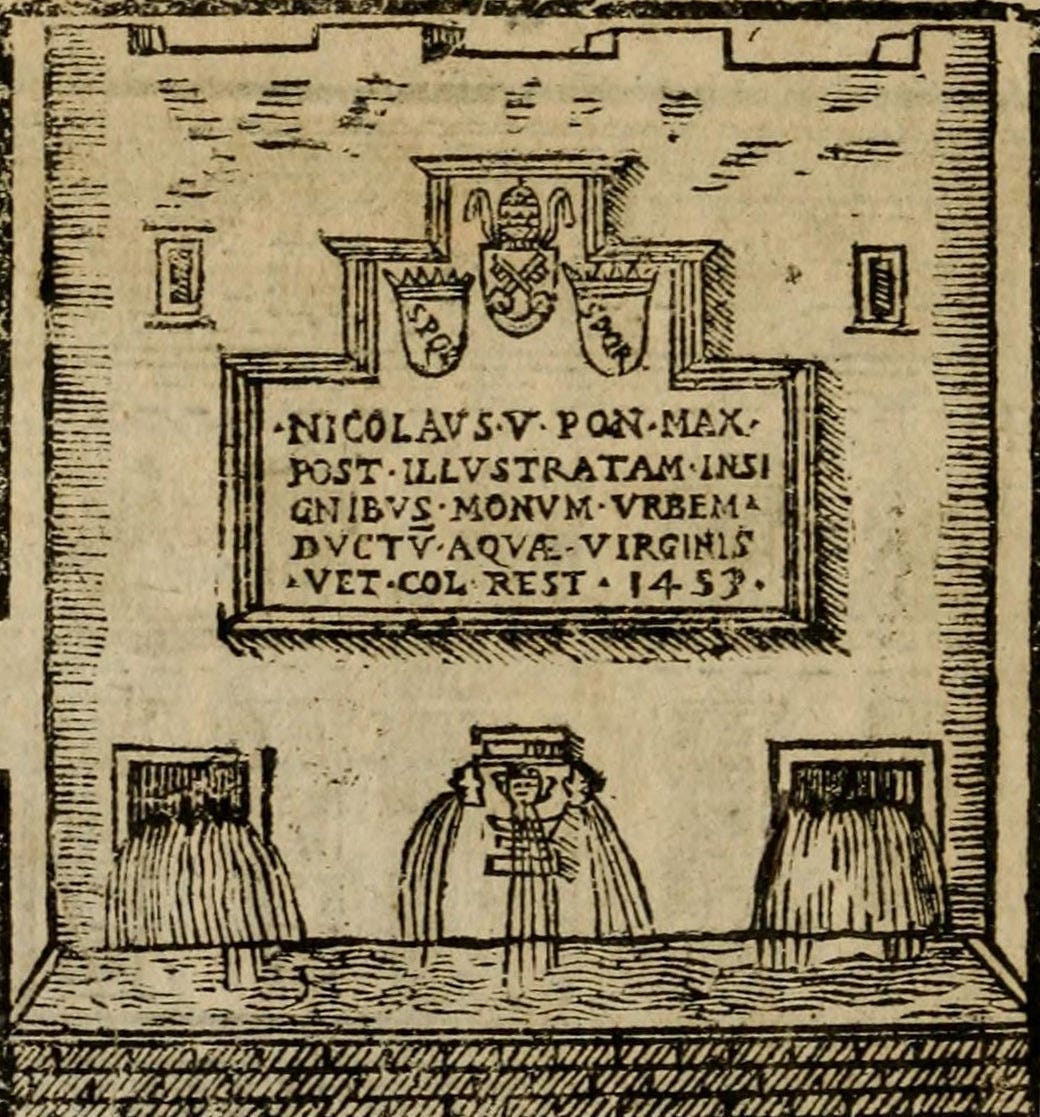

While works to properly restore the flow of the aqueduct would occupy multiple pontificates, it was in 1453 that Pope Nicholas V, advised by Genoese architect and polymath Leon Battista Alberti, commissioned a modest fountain to mark the new terminus of the Acqua Vergine at the aforementioned crossroads, crowned by a commemorative plaque carved with the straightforward inscription:

“Pope Nicholas V, having embellished the city with worthy monuments, in 1453 restored the Aqua Virgo from her ancient state of abandon”

Thus would the fountain of the tre vie remain for over two hundred years. It was not, however, a purely aesthetic addition, but an entirely functional amenity for the Romans who dwelled in the district. With household running water still many centuries away, the fountain was an essential source of drinking water.

Over the course of a hundred and seventeen years, a succession of Popes would fully restore the Acqua Vergine. A significant section of the channel was repaired under Sixtus IV, whose coat of arms marking this can still be seen a short walk behind the Trevi Fountain on Via del Nazareno today. Pius IV commenced an even grander project to restore the aqueduct all the way to its source, which was at last completed in 1570 under Pius V.

The barebones of the urban square where the Fountain stands today were in place by the 16th century, however with one key difference — the fountain was oriented 90° to the West, facing towards Via del Corso. But Rome was changing. Her needs were evolving, and her standards were raising.

The Bernini Touch

At the height of the Counter-Reformation, with the balance of the Papacy shifting from the clerical to the regal element, the 17th century would see the true beginning of the ‘monumentalisation’ of Rome for the first time since the Caesars.

An important mark of this was the increasing use of the Quirinal Palace over the Vatican as the residence of the Popes. With the Trevi Fountain being located within sight of the palace and at the foot of the Quirinal Hill itself, by the pontificate of Urban VIII (1623-1644) the rather humble and positively medieval look of the Trevi piazza was a source of increasing awkwardness amid the glories of Baroque Rome.

In 1640, Urban could stand it no more, and commissioned the greatest sculptor of the century, Gian Lorenzo Bernini, to solve this aesthetic problem. Unfortunately, the death of the Pope and the election of his staunch enemy — Innocent X — just four years later would abruptly sink the project before it had barely begun.

Indeed the only lasting imprint of Bernini here was the re-orientation of the piazza to its current alignment, facing the Quirinal Hill. It was also perhaps a blessing in disguise, as Urban had directed Bernini to procure the building materials for the planned fountain by demolishing the tomb of Caecilia Metella outside the city. The cancellation of the project thus spared what is today the most substantial ancient monument to survive on the Via Appia.

As is traditionally the case with public works in Italy, what followed was near interminable delay, as repeated proposals generated excitement, only to fall through due to petulance. It would take both leadership and will to lift the world’s grandest fountain off the drawing board — but finally, with the election of Lorenzo Corsini as Pope Clement XII, on the 12th July 1730, Rome would at last have both…

Celebration and Decoration

The pontificate of Clement XII, while lasting only ten years, was among the most effective in the history of the church. Hailing from the entrepreneurial Corsini family of Florence, Clement was an exceptionally able administrator, despite his physical frailty.

Under his reign, incompetent ministers were replaced, corruption was harshly cracked down upon, and the Papal finances were restored to health after years of mismanagement, permitting the return of large scale public works to Rome again.

Armed with considerable political capital, Clement turned his attention to the Trevi Question, announcing a public competition to determine its design.

Chief among the entries were proposals by the esteemed Ferdinando Fuga of Florence and Luigi Vanvitelli of Naples. Contrary to expectation however, the commission was awarded in 1732 to the young and otherwise little known Nicola Salvi, in a move quite possibly motivated by a desire for the project to be handled by a Roman rather than foreign architect.

With Rome by now broadly covered by regular and convenient fountains, or fontanelle, for the supply of potable water, and lavatoi basins for washing clothes, the city had come far since the beleaguered and squalid days of the medieval era. As a result, the new fountain was an occasion to celebrate this progress, by means of a monument that employed water not for logistics but for decoration, and cement the continuity of Rome from ancient to modern times that the Acqua Vergine itself represented.

With his finger ever on the fiscal pulse, the Pope decided that the Fountain would be funded not out of the Treasury, but from the proceeds of a popular Roman tradition — the lotto. Thus did the gambling habits of the Roman people finance their most graceful monument, yielding 17,646 scudi for the cause.

In a sign once more of the commitment men once had to long term vision, neither Clement nor Salvi would live to see the completion of the Trevi Fountain. That honour would fall to Pope Clement XIII — the successor of Clement XII’s own successor Benedict XIV — who officially inaugurated the Trevi Fountain on the 22nd May 1762.

Let us now read this greatest of monuments from the top, working our way all eighty five feet down.

A Temple of Water

Beneath the majestic heraldic arms of the House of Corsini, supported by angels and crowned by the Papal Tiara, is the dedicatory inscription of the Pope to whom said arms belonged: